Chelsea Margaret Bodnar is made of blood, meat, and bones — the usual suspects. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in: The Bennington Review, The Birds We Piled Loosely, Freezeray, Leopardskin & Limes, Menacing Hedge, and NANO Fiction, among others.

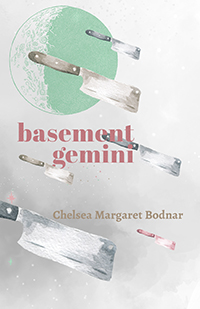

You recently published your debut collection of poetry, Basement Gemini (Hyacinth Girl Press). Tell us a bit about the chapbook and how it came into being.

You recently published your debut collection of poetry, Basement Gemini (Hyacinth Girl Press). Tell us a bit about the chapbook and how it came into being.

Well, I wrote Basement Gemini at a time when I was thinking very extensively about The Ring. I think it’s a fascinating movie, and no, I haven’t seen the original Japanese version. I’m a straight-up American Ring poseur. Anyways, The Ring is really interesting to me because of the ambiguity of its message. The takeaway is essentially that a little girl has been abused and ultimately murdered, but the twist is that she was presumably inherently evil the whole time, and you end up with this weird message/ethical dilemma about misplaced empathy, feminine power, and nature vs. nurture. At the end of the day, though, no matter how evil and powerful she was, Samara couldn’t get herself out of that well.

I remember watching it at age twelve when it came out. I was a total tomboy and actively discouraged being perceived as feminine, but lots of horror movies (think The Ring, Carrie, and even Psycho, in a deferred kind of way) reinforce that femininity can be dangerous, which is problematic, obviously, but also weirdly empowering. Basement Gemini was kind of born out of that idea — the simultaneous, seemingly-contradictory-but-not-really victimization, vilification, and empowerment of women that’s encountered so often in horror. I was also reading Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film by Carol J. Clover around the time I was writing the chapbook, which provides a pretty interesting critical look at the genre.

I love the way Basement Gemini explores female agency and voice through horror movie tropes. What draws you to horror?

I’ve always been a big fan of horror — particularly the supernatural variety. I’m an atheist and a devout nonbeliever in all things superstitious, but at the same time, the paranormal and/or demonic makes for some very compelling metaphors. My ideal horror movie involves a house, a ghost, and something unsavory that’s been repressed or glossed over. The idea that there could exist repercussions for abuse/violence/suffering that transcend societal action (or inaction) is kind of a satisfying notion, isn’t it? I’m thinking What Lies Beneath — you’re a young woman, you get murdered by your professor/lover, you come back as a ghost and exact vengeance with the help of his wife. Suddenly you’ve got a level of agency that goes way beyond being a thing that violence is done upon. It’s a fantasy of cosmic justice, or a cautionary tale with the message “don’t kill women,†depending on how you look at it.

That being said, I’ve watched a lot of very bad horror films with immense enjoyment. My favorites are probably The Manitou and Frozen in Fear, aka The Flying Dutchman. Sometimes I just like the performance and spectacle of putting together these tropes and seeking a quick buck. It can be kind of charming. Fitting the same tropes horror films utilize into poetry was a fun time, and I also realized I actually had a lot to say through them.

Since all of the poems are untitled, it allows one poem to flow into the next with the chapbook feeling like a single cohesive piece. How did you decide to leave the poems untitled? Did you always know they would be part of a large whole?

The (possibly disappointing) answer is that I’m terrible at titling and my natural tendency is to title via abysmal jokes/puns, which felt wrong with this project. I’m always playing chicken with my impulse to succumb to absurdity, and sometimes the temptation wins out. It’s like a less dire, more embarrassing version of Freud’s death drive.

I didn’t know these poems would be part of a chapbook, since I had no idea I’d be able to write that many thematically-similar pieces. I wrote the poems in Basement Gemini more or less in one unbroken period of writing (over a few months), without producing any unfitting poems in-between. I’ve written some poems that wouldn’t be out of place in Basement Gemini since then, but when I was writing this chapbook, I was in a phase of exclusively writing horror poems, whereas at present, it’s a theme I occasionally dip into but haven’t since committed to as fully.

What lessons did you learn in the process of putting together and publishing your debut collection of poetry? What was the biggest challenge in finishing the project?

The hardest thing about putting together a collection of poetry, for me, was knowing when to stop editing. I kept finding little moments where the rhythm was off, or the word I used wasn’t as precise as I wanted. I also had to cut some poems that I liked in order to make room for poems that fit better within the project. I also learned that it’s sometimes very hard to get other people to read your poem over and over again when you’ve only made minute changes (if they’re not your editor/publisher, that is). So yeah, letting go of my editing powers was probably the biggest challenge.

Can you talk a little about how you approach writing a poem? What launches you into a poem? How do you decide when it’s done?

I’ve written a surprising number of poems on my phone while on the bus. I can pretty much only write digitally — it’s a lot easier to make a large number of quick edits. As romantic as I find the idea of pens, stationary, typewriters, etc., I just can’t hack it. As for what launches me into a poem, I’m really not sure. There are things I’d love to be able to write poems about, but for one reason or another, I just can’t. I really wish I could write a book of poetry about Star Trek. That’d be rad. I write poems when I’ve got something on my mind, usually a specific feeling that something in my life evoked, e.g. I wrote a poem about incels the other day. Poems are done when they start to feel forced, after I edit the hell out of them & read them out loud to myself several times to make sure they flow (my poor downstairs neighbors), and, of course, when they end on a HOT TAKE, lol… I’m kind of kidding.

How did you get started as a writer? Why do you personally write poetry?

I remember slacking off in my 7th grade English class by reading the poetry section in the back of the textbook — a unit we never got to during actual class time. I specifically remember memorizing the poem The Broncho That Would Not Be Broken by Vachel Lindsay instead of paying attention, which was a weird choice, but I still have bits of it rattling around in my head to this day. I ended up going to Pitt and getting a BA in creative writing because Having A Degree was important to me at the time, but I wanted it to be in something that I actually liked, to the consternation of my academic advisor.

I think I probably write poetry because I derive a lot of enjoyment out of coming up with very precise ways to describe my feelings and perceptions in a manner that hopefully resonates with other people. That and I’m a sucker for novel combinations of language.

Do you feel community is important as a writer? How do you stay connected?

Honestly, when I try to engage with the writing community, oftentimes I feel kind of performative and terrible, which is a personal failing, I suppose. I belong to a couple of Facebook writing groups, and sometimes I share writing there, but I think the vestiges of my much-improved social anxiety still catch up to me where the writing community is concerned.

Name a poet you would like more readers to know about.

Cynthia Cruz! She’s my favorite writer and one of the only poets whose work I religiously follow.

What can the world expect from you in the future?

At the moment, I’ve got two chapbook-length, relatively thematically-cohesive collections of poetry I’ve written within the past year or so. One of them covers a variety of mental health topics, namely dissociation, depression, and social/general anxiety, and the sense of alienation and unreality that accompanies my own experiences with mental illness, in addition to the alienation inherent in language and self-expression.

I’ve also got a chapbook I’m still working on that’s made up of poems that use the icebreaker prompts from the dating app OkCupid as titles. That one is mostly about the failure of interpersonal relationships to provide adequate fulfillment — the fantasy of idealized close relationships (romantic and platonic) versus the realization that using other people as tools to tackle your issues is unhealthy. Our culture constantly reinforces the idea that each individual is a half of a whole, which is pretty messed-up. I feel like a good 75% of commercials hint that you might find True Love if you buy the product they’re selling, or at the very least, you’ll get laid.

I was in a long-term relationship up until not too long ago, and I was also in a bad place with my mental health for a pretty significant portion of my life. I’ve been successfully living alone for close to two years now, and I’ve been doing a lot of work on myself with therapy and medication. I was terrified that my writing would suffer if my mental health improved, honestly, which feels a little cliché/ridiculous to say, but I’ve been doing better than I thought possible lately, and I’m still writing.